1st Amendment

Madison’s version of the speech and presss clauses, introduced in the House of Representatives on June 8, 1789, provided: “The people shall not be

deprived or abridged of their right to speak, to write, or to publish their sentiments; and the freedom of the press, as one of the great bulwarks

1 The special committee rewrote the language to some extent, adding other provisions from Madison’s draft, to

make it read: “The freedom of speech and of the press, and the right of the people peaceably to assemble and consult for their common good,

and to apply to the Government for redress of grievances, shall not be infringed.” 2 In this form it went to the Senate, which rewrote it to read:

“That Congress shall make no law abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press, or the right of the people peaceably to assemble and

consult for their common good, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.” 3 Subsequently, the religion clauses and these

clauses were combined by the Senate. 4 The final language was agreed upon in conference.

Debate in the House is unenlightening with regard to the meaning the Members ascribed to the speech and press clause and there is no

record of debate in the Senate. 5 In the course of debate, Madison warned against the dangers which would arise “from discussing and

proposing abstract propositions, of which the judgment may not be convinced. I venture to say, that if we confine ourselves to an enumeration

of simple, acknowledged principles, the ratification will meet with but little difficulty.” 6 That the “simple, acknowledged principles” embodied in

the First Amendment have occasioned controversy without end both in the courts and out should alert one to the difficulties latent in such

spare language. Insofar as there is likely to have been a consensus, it was no doubt the common law view as expressed by Blackstone.

1021 "The liberty of the press is indeed essential to the nature of a free state; but this consists in laying no previous restraints

upon publications, and not in freedom from censure for criminal matter when published. Every freeman has an undoubted right to lay what

sentiments he pleases before the public; to forbid this, is to destroy the freedom of the press: but if he publishes what is improper,

mischievous, or illegal, he must take the consequences of his own temerity. To subject the press to the restrictive power of a licenser, as was

formerly done, both before and since the Revolution, is to subject all freedom of sentiment to the prejudices of one man, and make him the

arbitrary and infallible judge of all controverted points in learning, religion and government. But to punish as the law does at present any

dangerous or offensive writings, which, when published, shall on a fair and impartial trial be adjudged of a pernicious tendency, is necessary

for the preservation of peace and good order, of government and religion, the only solid foundations of civil liberty. Thus, the will of individuals

is still left free: the abuse only of that free will is the object of legal punishment. Neither is any restraint hereby laid upon freedom of thought or

inquiry; liberty of private sentiment is still left; the disseminating, or making public, of bad sentiments, destructive to the ends of society, is the

crime which society corrects.”

1022 7 Whatever the general unanimity on this proposition at the time of the proposal of and ratification of the First Amendment, 8

it appears that there emerged in the course of the Jeffersonian counterattack on the Sedition Act 9 and the use by the

Adams Administration of the Act to prosecute its political opponents, 10 something of a libertarian theory of freedom of speech and

press, 11 which, however much the Jeffersonians may have departed from it upon assuming power, 12 was to blossom into the theory

undergirding Supreme Court First Amendment jurisprudence in modern times. Full acceptance of the theory that the Amendment operates not

only to bar most prior restraints of expression but subsequent punishment of all but a narrow range of expression, in political discourse and

indeed in all fields of expression, dates from a quite recent period, although the Court’s movement toward that position began in its

consideration of limitations on speech and press in the period following World War I. 13

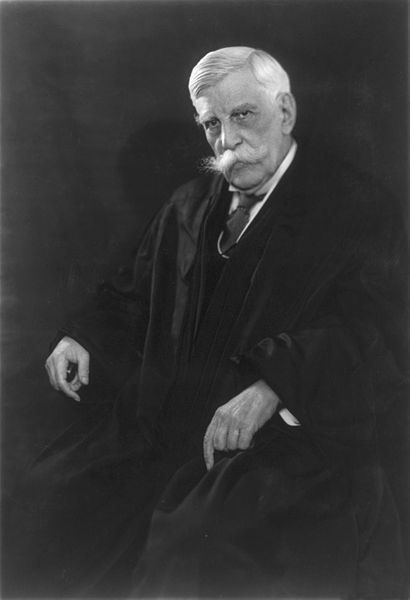

1023 Thus, in 1907 Justice Holmes could observe that even if the Fourteenth Amendment embodied prohibitions similar to the

First Amendment, “still we should be far from the conclusion that the plaintiff in error would have us reach. In the first place, the main purpose

of such constitutional provisions is ‘to prevent all such previous restraints upon publications as had been practiced by other governments,’ and

they do not prevent the subsequent punishment of such as may be deemed contrary to the public welfare . . . . The preliminary freedom

extends as well to the false as to the true; the subsequent punishment may extend as well to the true as to the false. This was the law of

criminal libel apart from statute in most cases, if not in all.” 14 But as Justice Holmes also observed, “[t]here is no constitutional right to

have all general propositions of law once adopted remain unchanged.” 15 But in Schenck v. United States, 16 the first of the post–

World War I cases to reach the Court, Justice Holmes, in the opinion of the Court, while upholding convictions for violating the Espionage

Act by attempting to cause insubordination in the military service by circulation of leaflets, suggested First Amendment restraints on

subsequent punishment as well as prior restraint.

1024 "It well may be that the prohibition of laws abridging the freedom of speech is not confined to previous restraints although to

prevent them may have been the main purpose . . . . We admit that in many places and in ordinary times the defendants in saying all that was

said in the circular would have been within their constitutional rights. But the character of every act depends upon the circumstances in which

it is done. The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theater and causing a panic. . . .

The question in every case is whether the words used are used in such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring

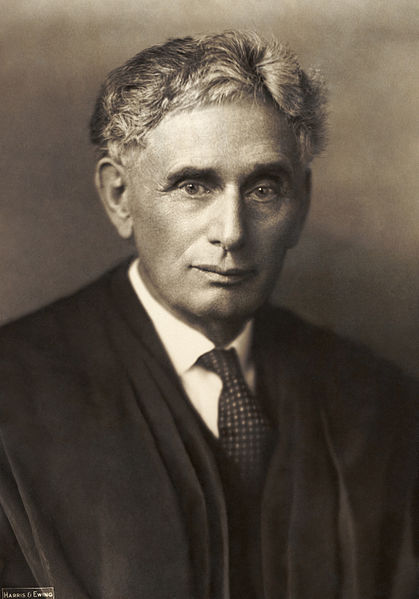

about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent.” Justice Holmes along with Justice Brandeis soon went into dissent in

their views that the majority of the Court was misapplying the legal standards thus expressed to uphold suppression of speech which offered

no threat of danger to organized institutions. 17 But it was with the Court’s assumption that the Fourteenth Amendment restrained the power

of the States to suppress speech and press that the doctrines developed. 18 At first, Holmes and Brandeis remained in dissent, but in

Fiske v. Kansas, 19 the Court sustained a First Amendment type of claim in a state case, and in Stromberg v. California, 20 a state law

was voided on grounds of its interference with free speech. 21 State common law was also voided, the Court in an opinion by

Justice Black asserting that the First Amendment enlarged protections for speech, press, and religion beyond those enjoyed under English

common law. 22 Development over the years since has been uneven, but by 1964 the Court could say with unanimity: “we consider this case

against the background of a profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and

wide–open, and that it may well include vehement, caustic and sometimes unpleasantly sharp attacks on government and public officials, 23

1025 And in 1969, it was said that the cases “have fashioned the principle that the constitutional guarantees of free speech and

free press do not permit a State to forbid or proscribe advocacy of the use of force or of law violation except where such advocacy is directed

to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.” 24 This development and its myriad applications

are elaborated in the following sections.

Freedom of Expression: The Philosophical Basis

Probably no other provision of the Constitution has given rise to so many different views with respect to its underlying philosophical

foundations, and hence proper interpretive framework, as has the guarantee of freedom of expression—the free speech and free press

clauses. 25 The argument has been fought out among the commentators. “The outstanding fact about the First Amendment today is that the

Supreme Court has never developed any comprehensive theory of what that constitutional guarantee means and how it should be applied in

concrete cases.” 26 Some of the commentators argue in behalf of a complex of values, none of which by itself is sufficient to support a broad

–based protection of freedom of expression. 27

1026 Others would limit the basis of the First Amendment to one only among a constellation of possible values and

would therefore limit coverage or degree of protection of the speech and press clauses. For example, one school of thought believes that,

because of the constitutional commitment to free self–government, only political speech is within the core protected area, 28 although some

commentators tend to define more broadly the concept of “political” than one might suppose from the word alone. Others recur to the writings

of Milton and Mill and argue that protecting speech, even speech in error, is necessary to the eventual ascertainment of the truth, through

conflict of ideas in the marketplace, a view skeptical of our ability to ever know the truth. 29 A broader–grounded view is variously expounded

by scholars who argue that freedom of expression is necessary to promote individual self–fulfillment, such as the concept that when speech is

freely chosen by the speaker to persuade others it defines and expresses the “self,” promotes his liberty, 30 or the concept of “self–

realization,” the belief that free speech enables the individual to develop his powers and abilities and to make and influence decisions

regarding his destiny. 31 The literature is enormous and no doubt the Justices as well as the larger society are influenced by it, and yet the

decisions, probably in large part because they are the collective determination of nine individuals, seldom clearly reflect a principled and

consistent acceptance of any philosophy.

Freedom of Expression: Is There a Difference Between Speech and Press

Utilization of the single word “expression” to reach speech, press, petition, association, and the like, raises the central question of whether the

free speech clause and the free press clause are coextensive; does one perhaps reach where the other does not?

1027 It has been much debated, for example, whether the “institutional press” may assert or be entitled to greater freedom from

governmental regulations or restrictions than are non–press individuals, groups, or associations. Justice Stewart has argued: “That the

First Amendment speaks separately of freedom of speech and freedom of the press is no constitutional accident, but an acknowledgment of

the critical role played by the press in American society. The Constitution requires sensitivity to that role, and to the special needs of the press

in performing it effectively.” 32 But as Chief Justice Burger wrote: “The Court has not yet squarely resolved whether the Press Clause

confers upon the ‘institutional press’ any freedom from government restraint not enjoyed by all others.” 33

Several Court holdings do firmly point to the conclusion that the press clause does not confer on the press the power to compel government

to furnish information or to give the press access to information that the public generally does not have. 34 Nor in many respects is the press

entitled to treatment different in kind than the treatment any other member of the public may be subjected to. 35 “Generally applicable laws do

not offend the First Amendment simply because their enforcement against the press has incidental effects.” 36 Yet, it does seem clear that to

some extent the press, because of the role it plays in keeping the public informed and in the dissemination of news and information, is entitled

to particular if not special deference that others are not similarly entitled to, that its role constitutionally entitles it to governmental “sensitivity,”

to use Justice Stewart’s word. 37

1028 What difference such a recognized “sensitivity” might make in deciding cases is difficult to say.

The most interesting possibility lies in the area of First Amendment protection of good faith defamation. 38 Justice Stewart argued that the

Sullivan privilege is exclusively a free press right, denying that the “constitutional theory of free speech gives an individual any immunity from

liability for libel or slander.” 39 To be sure, in all the cases to date that the Supreme Court has resolved, the defendant has been, in some

manner, of the press, 40 but the Court’s decision that corporations are entitled to assert First Amendment speech guarantees against federal

and, through the Fourteenth Amendment, state regulations causes the evaporation of the supposed “conflict” between speech clause

protection of individuals only and of press clause protection of press corporations as well as of press individuals. 41 The issue, the Court

wrote, was not what constitutional rights corporations have but whether the speech which is being restricted is expression that the First

Amendment protects because of its societal significance. Because the speech concerned the enunciation of views on the conduct of

governmental affairs, it was protected regardless of its source; while the First Amendment protects and fosters individual self– expression as a

worthy goal, it also and as important affords the public access to discussion, debate, and the dissemination of information and ideas. Despite

Bellotti’s emphasis upon the nature of the contested speech being political, it is clear that the same principle,

1029 the right of the public to receive information, governs nonpolitical, corporate speech. 42

With some qualifications, therefore, it is submitted that the speech and press clauses may be analyzed under an umbrella “expression”

standard, with little, if any, hazard of missing significant doctrinal differences.

The Doctrine of Prior Restraint

“[L]iberty of the press, historically considered and taken up by the Federal Constitution, has meant, principally although not exclusively,

immunity from previous restraints or censorship.” 43 “Any system of prior restraints of expression comes to this Court bearing a heavy

presumption against its constitutional validity.” 44 Government “thus carries a heavy burden of showing justification for the imposition of such a

restraint.” 45 Under the English licensing system, which expired in 1695, all printing presses and printers were licensed and nothing could be

published without prior approval of the state or church authorities. The great struggle for liberty of the press was for the right to publish without

a license that which for a long time could be published only with a license. 46

The United States Supreme Court’s first encounter with a law imposing a prior restraint came in Near v. Minnesota ex rel. Olson, 47 in which

a five–to–four majority voided a law authorizing the permanent enjoining of future violations by any newspaper or periodical once found to

have published or circulated an “obscene, lewd and lascivious” or a “malicious, scandalous and defamatory” issue. An injunction had been

issued after the newspaper in question had printed a series of articles tying local officials to gangsters. While the dissenters maintained that

the injunction constituted no prior restraint, inasmuch as that doctrine applied to prohibitions of publication without advance approval of an

executive official, 48 the majority deemed the difference of no consequence, since in order to avoid a contempt citation the newspaper would

have to clear future publications in advance with the judge. 49

1030 Liberty of the press to scrutinize closely the conduct of public affairs was essential, said Chief Justice Hughes for the

Court. “[T]he administration of government has become more complex, the opportunities for malfeasance and corruption have multiplied,

crime has grown to most serious proportions, and the danger of its protection by unfaithful officials and of the impairment of the fundamental

security of life and property by criminal alliances and official neglect, emphasizes the primary need of a vigilant and courageous press,

especially in great cities. The fact that the liberty of the press may be abused by miscreant purveyors of scandal does not make any the less

necessary the immunity of the press from previous restraint in dealing with official misconduct. Subsequent punishment for such abuses as

may exist is the appropriate remedy, consistent with constitutional privilege.” 50 The Court did not undertake to explore the kinds of

restrictions to which the term “prior restraint” would apply nor to do more than assert that only in “exceptional circumstances” would prior

restraint be permissible. 51 Nor did subsequent cases substantially illuminate the murky interior of the doctrine. The doctrine of prior restraint

was called upon by the Court as it struck down a series of loosely drawn statutes and ordinances requiring licenses to hold meetings and

parades and to distribute literature, with uncontrolled discretion in the licensor whether or not to issue them, and as it voided other restrictions

on First Amendment rights. 52 The doctrine that generally emerged was that permit systems—prior licensing, if you will—were constitutionally

valid so long as the discretion of the issuing official was limited to questions of times, places, and manners. 53

1031 The most recent Court encounter with the doctrine in the national security area occurred when the Government attempted

to enjoin press publication of classified documents pertaining to the Vietnam War 54 and, although the Court rejected the effort, at least five

and perhaps six Justices concurred on principle that in some circumstances prior restraint of publication would be constitutional. 55 But no

cohesive doctrine relating to the subject, its applications, and its exceptions has yet emerged.

Injunctions and the Press in Fair Trial Cases.—Confronting a claimed conflict between free press and fair trial guarantees, the Court

unanimously set aside a state court injunction barring the publication of information that might prejudice the subsequent trial of a criminal

defendant. 56 Though agreed on result, the Justices were divided with respect to whether “gag orders” were ever permissible and if so what

the standards for imposing them were.

1032 The opinion of the Court utilized the Learned Hand formulation of the "clear and present danger" test 57 and considered as

factor in any decision on the imposition of a restraint upon press reporters (a) the nature and extent of pretrial news coverage, (b) whether

other measures were likely to mitigate the harm, and (c) how effectively a restraining order would operate to prevent the threatened danger.58

One seeking a restraining order would have a heavy burden to meet to justify such an action, a burden that could be satisfied only on a

showing that with a prior restraint a fair trial would be denied, but the Chief Justice refused to rule out the possibility of showing the kind of

threat that would possess the degree of certainty to justify restraints. 59 Justice Brennan’s major concurring opinion flatly took the position

that such restraining orders were never permissible. Commentary and reporting on the criminal justice system is at the core of

First Amendment values, he would hold, and secrecy can do so much harm “that there can be no prohibition on the publication by the press of

any information pertaining to pending judicial proceedings or the operation of the criminal justice system, no matter how shabby the means by

which the information is obtained.” 60 The extremely narrow exceptions under which prior restraints might be permissible relate to probable

national harm resulting from publication, the Justice continued; because the trial court could adequately protect a defendant’s right to a fair

trial through other means even if there were conflict of constitutional rights the possibility of damage to the fair trail right would be so

speculative that the burden of justification could not be met. 61

1033 While the result does not foreclose the possibility of future "gag orders," it does lessen the number to be expected

and shifts the focus to other alternatives for protecting trial rights. 62 On a different level, however, are orders restraining the press as a party

to litigation in the dissemination of information obtained through pretrial discovery. In Seattle Times Co. v. Rhinehart, 63 the Court

determined that such orders protecting parties from abuses of discovery require “no heightened First Amendment scrutiny.” 64 Obscenity and

Prior Restraint.—Only in the obscenity area has there emerged a substantial consideration of the doctrine of prior restraint and the doctrine’s

use there may be based upon the proposition that obscenity is not a protected form of expression. 65 In Kingsley Books v. Brown, 66

the Court upheld a state statute which, while it embodied some features of prior restraint, was seen as having little more restraining effect

than an ordinary criminal statute; that is, the law’s penalties applied only after publication. But in Times Film Corp. v. City of Chicago, 67

a divided Court specifically affirmed that, at least in the case of motion pictures, the First Amendment did not proscribe a licensing system

under which a board of censors could refuse to license for public exhibition films which it found to be obscene. Books and periodicals may also

be subjected to some forms of prior restraint, 68 but the thrust of the Court’s opinions in this area with regard to all forms of communication

has been to establish strict standards of procedural protections to ensure that the censoring agency bears the burden of proof on obscenity,

that only a judicial order can restrain exhibition, and that a prompt final judicial decision is assured. 69

1034 Subsequent Punishment: Clear and Present Danger and Other Tests

Granted that the context of the controversy over freedom of expression at the time of the ratification of the First Amendment was almost

exclusively limited to the problem of prior restraint, still the words speak of laws “abridging” freedom of speech and press and the modern

adjudicatory disputes have been largely fought out over subsequent punishment. “The mere exemption from previous restraints cannot be all

that is secured by the constitutional provisions, inasmuch as of words to be uttered orally there can be no previous censorship, and the liberty

of the press might be rendered a mockery and a delusion, and the phrase itself a byword, if, while every man was at liberty to publish what he

pleased, the public authorities might nevertheless punish him for harmless publications. . . .

“[The purpose of the speech–press clauses] has evidently been to protect parties in the free publication of matters of public concern, to secure

their right to a free discussion of public events and public measures, and to enable every citizen at any time to bring the government and any

person in authority to the bar of public opinion by any just criticism upon their conduct in the exercise of the authority which the people have

conferred upon them. . . . The evils to be prevented were not the censorship of the press merely, but any action of the government by means

of which it might prevent such free and general discussion of public matters as seems absolutely essential to prepare the people for an

intelligent exercise of their rights as citizens.” 70 A rule of law permitting criminal or civil liability to be imposed upon those who speak or write

on public issues and their superintendence would lead to “self–censorship” by all which would not be relieved by permitting a defense of truth.

“Under such a rule, would–be critics of official conduct may be deterred from voicing their criticism, even though it is believed to be true and

even though it is in fact true, because of doubt whether it can be proved in court or fear of the expense of having to do so . . . . The rule thus

dampens the vigor and limits the variety of public debate.” 71

1035 “Persecution for the expression of opinions seems to me perfectly logical. If you have no doubt of your premises or your

power and want a certain result with all your heart you naturally express your wishes in law and sweep away all opposition. To allow

opposition by speech seems to indicate that you think the speech impotent, as when a man says that he has squared the circle, or that you do

not care whole– heartedly for the result, or that you doubt either your power or your premises. But when men have realized that time has upset

many fighting faiths, they may come to believe even more than they believe the very foundations of their own conduct that the ultimate good

desired is better reached by free trade in ideas, that the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of

the market, and that truth is the only ground upon which their wishes safely can be carried out. That at any rate is the theory of our

Constitution.” 72 “Those who won our independence believed that the final end of the State was to make men free to develop their faculties;

and that in its government the deliberative forces should prevail over the arbitrary. They valued liberty both as an end and as a means.

They believed liberty to be the secret of happiness and courage to be the secret of liberty. They believed that freedom to think as you will and

to speak as you think are means indispensable to the discovery and spread of political truth; that without free speech and assembly discussion

would be futile; that with them, discussion affords ordinarily adequate protection against the dissemination of noxious doctrine; that the

greatest menace to freedom is an inert people; that public discussion is a political duty; and that this should be a fundamental principle of the

American government.

They recognized the risks to which all human institutions are subject. But they knew that order cannot be secured merely through fear of

punishment for its infraction; that it is hazardous to discourage thought, hope and imagination; that fear breeds repression; that repression

breeds hate; that hate menaces stable government; that the path of safety lies in the opportunity to discuss freely supposed grievances and

proposed remedies; and that the fitting remedy for evil counsels is good ones. Believing in the power of reason as applied through public

discussion, they eschewed silence coerced by law—the argument of force in its worst form.

1036 Recognizing the occasional tyrannies of governing majorities, they amended the Constitution so that free speech and

assembly should be guaranteed.” 73 "But, although the rights of free speech and assembly are fundamental, they are not in their nature

absolute. Their exercise is subject to restriction, if the particular restriction proposed is required in order to protect the State from destruction

or from serious injury, political, economic or moral.” 74 The fixing of a standard is necessary, by which it can be determined what degree of evil

is sufficiently substantial to justify resort to abridgment of speech and press and assembly as a means of protection and how clear and

imminent and likely the danger is. 75 That standard has fluctuated over a period of some fifty years now and it cannot be asserted with a great

degree of confidence that the Court has yet settled on any firm standard or any set of standards for differing forms of expression. 76

The cases are instructive of the difficulty.

Clear and Present Danger.—Certain expression, oral or written, may incite, urge, counsel, advocate, or importune the commission of criminal

conduct; other expression, such as picketing, demonstrating, and engaging in certain forms of “symbolic” action may either counsel the

commission of criminal conduct or itself constitute criminal conduct. Leaving aside for the moment the problem of “speech–plus”

communication, it becomes necessary to determine when expression that may be a nexus to criminal conduct is subject to punishment and

restraint. At first, the Court seemed disposed in the few cases reaching it to rule that if the conduct could be made criminal, the advocacy of or

promotion of the conduct could be made criminal. 77 Then, in Schenck v. United States, 78 in which defendants had been convicted of

seeking to disrupt recruitment of military personnel by dissemination of certain leaflets, Justice Holmes formulated the “clear and present

danger” test which has ever since been the starting point of argument. “The question in every case is whether the words used are used in

such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that

Congress has a right to prevent. It is a question of proximity and degree.” 79 The convictions were unanimously affirmed.

1037 One week later, the Court again unanimously affirmed convictions under the same Act with Justice Holmes speaking.

“[W]e think it necessary to add to what has been said in Schenck v. United States . . . only that the First Amendment while prohibiting

legislation against free speech as such cannot have been, and obviously was not, intended to give immunity for every possible use of

language.

We venture to believe that neither Hamilton nor Madison, nor any other competent person then or later, ever supposed that to make criminal

the counseling of a murder within the jurisdiction of Congress would be an unconstitutional interference with free speech.” 80

And in Debs v. United States, 81 Justice Holmes was found referring to “the natural and intended effect” and “probable effect” of the

condemned speech in common–law tones.

But in Abrams v. United States, 82 Justices Holmes and Brandeis dissented upon affirmance of the convictions of several alien

anarchists who had printed leaflets seeking to encourage discontent with United States participation in the War.

The majority simply referred to Schenck and Frohwerk to rebut the First Amendment argument, but the dissenters urged that the Government

had made no showing of a clear and present danger. Another affirmance by the Court of a conviction, the majority simply saying that “[t]he

tendency of the articles and their efficacy were enough for the offense,” drew a similar dissent. 83 Moreover, in Gitlow v. New York, 84 a

conviction for distributing a manifesto in violation of a

law making it criminal to advocate, advise, or teach the duty, necessity, or propriety of overthrowing organized government by force or

violence, the Court affirmed in the absence of any evidence regarding the effect of the distribution and in the absence of any contention that it

created any immediate threat to the security of the State. In so doing, the Court discarded Holmes’ test. “It is clear that the question in such

cases [as this] is entirely different from that involved in those cases where the statute merely prohibits certain acts involving the danger of

substantive evil, without any reference to language itself, and it is sought to apply its provisions to language used by the defendant for the

purpose of bringing about the prohibited results. . . . In such cases it has been held that the general provisions of the statute may be

constitutionally applied to the specific utterance of the defendant if its natural tendency and probable effect was to bring about the substantive

evil which the legislative body might prevent. . . .

1038 [T]he general statement in the Schenck Case . . . was manifestly intended . . . to apply only in cases of this class, and has no

application to those like the present, where the legislative body itself has previously determined the danger of substantive evil arising from

utterances of a specified character.” 85 Thus, a state legislative determination “that utterances advocating the overthrow of organized

government by force, violence, and unlawful means, are so inimical to the general welfare, and involve such danger of substantive evil that

they may be penalized in the exercise of its police power” was almost conclusive on the Court. 86 It is not clear what test, if any, the majority

would have utilized, although the “bad tendency” test has usually been associated with the case. In Whitney v. California, 87 the Court

affirmed a conviction under a criminal syndicalism statute based on defendant’s association with and membership in an organization which

advocated the commission of illegal acts, finding again that the determination of a legislature that such advocacy involves “such danger to the

public peace and the security of the State” was entitled to almost conclusive weight. In a technical concurrence which was in fact a dissent

from the opinion of the Court, Justice Brandeis restated the “clear and present danger” test. “[E]ven advocacy of violation [of the law] . . .

is not a justification for denying free speech where the advocacy falls short of incitement and there is nothing to indicate that the advocacy

would be immediately acted on . . . . In order to support a finding of clear and present danger it must be shown either that immediate serious

violence was to be expected or was advocated, or that the past conduct furnished reason to believe that such advocacy was then

contemplated.” 88 The Adoption of Clear and Present Danger.—

1039 The Court did not invariably affirm convictions during this period in cases like those under consideration. In Fiske v. Kansas,

89 it held that a criminal syndicalism law had been invalidly applied to convict one against whom the only evidence was the “class struggle”

language of the constitution of the organization to which he belonged. A conviction for violating a “red flag” law was voided as the statute was

found unconstitutionally vague. 90 Neither case mentioned clear and present danger. An “incitement” test seemed to underlie the opinion in

De Jonge v. Oregon, 91 upsetting a conviction under a criminal syndicalism statute for attending a meeting held under the auspices of an

organization which was said to advocate violence as a political method, although the meeting was orderly and no violence was advocated

during it. In Herndon v. Lowry, 92 the Court narrowly rejected the contention that the standard of guilt could be made the “dangerous

tendency” of one’s words, and indicated that the power of a State to abridge speech “even of utterances of a defined character must find its

justification in a reasonable apprehension of danger to organized government.”

Finally, in Thornhill v. Alabama, 93 a state anti–picketing law was invalidated because “no clear and present danger of destruction of life or

property, or invasion of the right of privacy, or breach of the peace can be thought to be inherent in the activities of every person who

approaches the premises of an employer and publicizes the facts of a labor dispute involving the latter.” During the same term, the Court

reversed the breach of the peace conviction of a Jehovah’s Witness who had played an inflammatory phonograph record to persons on the

street, the Court discerning no clear and present danger of disorder. 94

The stormiest fact situation faced by the Court in applying clear and present danger occurred in Terminiello v. City of Chicago, 95 in which a

five–to–four majority struck down a conviction obtained after the judge instructed the jury that a breach of the peace could be committed by

speech that “stirs the public to anger, invites dispute, brings about a condition of unrest, or creates a disturbance.” “A function of free speech

under our system of government,” wrote Justice Douglas for the majority, “is to invite dispute.

1040 It may indeed best serve its high purpose when it induces a condition of unrest, creates dissatisfaction with conditions as they

are, or even stirs people to anger. Speech is often provocative and challenging. It may strike at prejudices and preconceptions and have

profound unsettling effects as it presses for acceptance of an idea. That is why freedom of speech, though not absolute, . . . is nevertheless

protected against censorship or punishment, unless shown likely to produce a clear and present danger of a serious substantive evil that rises

far above public inconvenience, annoyance, or unrest.” 96 The dissenters focused on the disorders which had actually occurred as a result of

Terminiello’s speech, Justice Jackson saying: “Rioting is a substantive evil, which I take it no one will deny that the State and the City have

the right and the duty to prevent and punish . . . . In this case the evidence proves beyond dispute that danger of rioting and violence in

response to the speech was clear, present and immediate.” 97 The Jackson position was soon adopted in Feiner v. New York, 98 in which

Chief Justice Vinson said that “[t]he findings of the state courts as to the existing situation and the imminence of greater disorder coupled

with petitioner’s deliberate defiance of the police officers convince us that we should not reverse this conviction in the name of free speech.”

Contempt of Court and Clear and Present Danger.—The period during which clear and present danger was the standard by which to

determine the constitutionality of governmental suppression of or punishment for expression was a brief one, extending roughly from Thornhill

to Dennis. 99 But in one area it was vigorously, though not without dispute, applied to enlarge freedom of utterance and it is in this area that it

remains viable. In early contempt–of–court cases in which criticism of courts had been punished as contempt, the Court generally took the

position that even if freedom of speech and press was protected against governmental abridgment, a publication tending to obstruct the

administration of justice was punishable, irrespective of its truth. 100 But in Bridges v. California, 101 in which contempt citations had been

brought against a newspaper and a labor leader for statements made about pending judicial proceedings, Justice Black for a five–to–four

Court

1041 majority began with application of clear and present danger, which he interpreted to require that “the substantive evil must be

extremely serious and the degree of imminence extremely high before utterances can be punished.” 102 He noted that the “substantive evil

here sought to be averted . . . appears to be double: disrespect for the judiciary; and disorderly and unfair administration of justice.”

The likelihood that the court will suffer damage to its reputation or standing in the community was not, Justice Black continued, a

“substantive evil” which would justify punishment of expression. 103 The other evil, “disorderly and unfair administration of justice,” “is more

plausibly associated with restricting publications which touch upon pending litigation.” But the “degree of likelihood” of the evil being

accomplished was not “sufficient to justify summary punishment.” 104 In dissent, Justice Frankfurter accepted the application of clear

and present danger, but he interpreted it as meaning no more than a “reasonable tendency” test. “Comment however forthright is one thing.

Intimidation with respect to specific matters still in judicial suspense, quite another. . . . A publication intended to teach the judge a lesson, or

to vent spleen, or to discredit him, or to influence him in his future conduct, would not justify exercise of the contempt power. . . . It must refer

to a matter under consideration and constitute in effect a threat to its impartial disposition. It must be calculated to create an atmospheric

pressure incompatible with rational, impartial adjudication. But to interfere with justice it need not succeed. As with other offenses, the state

should be able to proscribe attempts that fail because of the danger that attempts may succeed.” 105

A unanimous Court next struck down the contempt conviction arising out of newspaper criticism of judicial action already taken, although

one case was pending after a second indictment. Specifically alluding to clear and present danger, while seeming to regard it as stringent a

test as Justice Black had in the prior case, Justice Reed wrote that the danger sought to be averted, a “threat to the impartial and orderly

administration of justice,” “has not the clearness and immediacy necessary to close the door of permissible public comment.” 106 Divided

again, the Court a year later set aside contempt convictions based on publication,

1042 while a motion for a new trial was pending, of inaccurate and unfair accounts and an editorial concerning the trial of a civil

case. “The vehemence of the language used is not alone the measure of the power to punish for contempt. The fires which it kindles must

constitute an imminent, and not merely a likely, threat to the administration of justice. The danger must not be remote or even probable; it

must immediately imperil.” 107 In Wood v. Georgia, 108 the Court again divided, applying clear and present danger to upset the contempt

conviction of a sheriff who had been cited for criticizing the recommendation of a county court that a grand jury look into African American

bloc voting, vote buying, and other alleged election irregularities. No showing had been made, said Chief Justice Warren, of “a

substantive evil actually designed to impede the course of justice.” The case presented no situation in which someone was on trial, there was

no judicial proceeding pending that might be prejudiced, and the dispute was more political than judicial. 109 A unanimous Court recently

seems to have applied the standard to set aside an contempt conviction of a defendant who, arguing his own case, alleged before the jury

that the trial judge by his bias had prejudiced his trial and that he was a political prisoner. Though the defendant’s remarks may have been

disrespectful of the court, the Supreme Court noted that “[t]here is no indication . . . that petitioner’s statements were uttered in a boisterous

tone or in any wise actually disrupted the court proceeding” and quoted its previous language about the imminence of the threat necessary to

constitute contempt. 110 Clear and Present Danger Revised: Dennis.—In Dennis v. United States, 111 the Court sustained the

constitutionality of the Smith Act, 112 which proscribed advocacy of the overthrow by force and violence of the government of the United

States, and upheld convictions under it.

1043 Dennis’ importance here is in the rewriting of the clear and present danger test. For a plurality of four,

Chief Justice Vinson acknowledged that the Court had in recent years relied on the Holmes–Brandeis formulation of clear and

present danger without actually overruling the older cases that had rejected the test; but while clear and present danger was the proper

constitutional test, that “shorthand phrase should [not] be crystallized into a rigid rule to be applied inflexibly without regard to the

circumstances of each case.” It was a relative concept. Many of the cases in which it had been used to reverse convictions had turned “on

the fact that the interest which the State was attempting to protect was itself too insubstantial to warrant restriction of speech.” 113 Here, in

contrast, “[o]verthrow of the Government by force and violence is certainly a substantial enough interest for the Government to limit

speech.” 114 And in combating that threat, the Government need not wait to act until the putsch is about to be executed and the plans are set

for action. “If Government is aware that a group aiming at its overthrow is attempting to indoctrinate its members and to commit them to a

course whereby they will strike when the leaders feel the circumstances permit, action by the Government is required.” 115 Therefore, what

does the phrase “clear and present danger” import for judgment? “Chief Judge Learned Hand, writing for the majority below, interpreted

the phrase as follows: ‘In each case [courts] must ask whether the gravity of the “evil,” discounted by its improbability, justifies such invasion

of free speech as is necessary to avoid the danger.’ 183 F.2d at 212. We adopt this statement of the rule.

As articulated by Chief Judge Hand, it is as succinct and inclusive as any other we might devise at this time. It takes into consideration

those factors which we deem relevant, and relates their significances. More we cannot expect from words.” 116 The “gravity of the evil,

discounted by its improbability” was found to justify the convictions. 117

1044 Balancing.—Clear and present danger as a test, it seems clear, was a pallid restriction on governmental power after

Dennis and it virtually disappeared from the Court’s language over the next twenty years. 118 Its replacement for part of this period was the

much disputed “balancing” test, which made its appearance in the year prior to Dennis in American Communications Ass’n v. Douds. 119

There the Court sustained a law barring from access to the NLRB any labor union if any of its officers failed to file annually an oath disclaiming

membership in the Communist Party and belief in the violent overthrow of the government. 120 For the Court, Chief Justice Vinson

rejected reliance on the clear and present danger test. “Government’s interest here is not in preventing the dissemination of Communist

doctrine or the holding of particular beliefs because it is feared that unlawful action will result therefrom if free speech is practiced. Its interest

is in protecting the free flow of commerce from what Congress considers to be substantial evils of conduct that are not the products of speech

at all. Section 9 (h), in other words, does not interfere with speech because Congress fears the consequences of speech; it regulates harmful

conduct which Congress has determined is carried on by persons who may be identified by their political affiliations and beliefs. The Board

does not contend that political strikes . . . are the present or impending products of advocacy of the doctrines of Communism or the expression

of belief in overthrow of the Government by force. On the contrary, it points out that such strikes are called by persons

1045 who, so Congress has found, have the will and power to do so without advocacy.” 121

The test, rather, must be one of balancing of interests. “When particular conduct is regulated in the interest of public order, and the regulation

results in an indirect, conditional, partial abridgement of speech, the duty of the courts is to determine which of these two conflicting interests

demands the greater protection under the particular circumstances presented.” 122 Inasmuch as the interest in the restriction, the

government’s right to prevent political strikes and the disruption of commerce, is much more substantial than the limited interest on the other

side in view of the relative handful of persons affected in only a partial manner, the Court perceived no difficulty upholding the statute. 123

Justice Frankfurter in Dennis 124 rejected the applicability of clear and present danger and adopted a balancing test. “The demands of

free speech in a democratic society as well as the interest in national security are better served by candid and informed weighing of the

competing interests, within the confines of the judicial process, than by announcing dogmas too inflexible for the non–Euclidian problems to

be solved.” 125 But the “careful weighing of conflicting interests” 126 not only placed in the scale the disparately–weighed interest of

government in self–preservation and the interest of defendants in advocating illegal action, which alone would have determined the balance,

it also involved the Justice’s philosophy of the “confines of the judicial process” within which the role of courts, in First Amendment litigation as

in other, is severely limited. Thus, “[f]ull responsibility” may not be placed in the courts “to balance the relevant factors and ascertain which

interest in the circumstances [is] to prevail.” “Courts are not representative bodies. They are not designed to be a good reflex of a democratic

society.” Rather, “[p]rimary responsibility for adjusting the interests which compete in the situation before us of necessity belongs to the

Congress.”127 Therefore, after considering at some length the factors to be balanced, Justice Frankfurter concluded: “It is not for us to

decide how we would adjust the clash of interests which this case presents were the primary responsibility for reconciling it ours. Congress

has determined that the danger created by advocacy of overthrow justifies the ensuing restriction on freedom of speech.

1046 The determination was made after due deliberation, and the seriousness of the congressional purpose is attested by the

volume of legislation passed to effectuate the same ends.” 128 Only if the balance struck by the legislature is “outside the pale of fair

judgment” 129 could the Court hold that Congress was deprived by the Constitution of the power it had exercised. 130

Thereafter, during the 1950’s and the early 1960’s, the Court utilized the balancing test in a series of decisions in which the issues were not,

as they were not in Douds and Dennis, matters of expression or advocacy as a threat but rather were governmental inquiries into associations

and beliefs of persons or governmental regulation of associations of persons, based on the idea that beliefs and associations provided

adequate standards for predicting future or intended conduct that was within the power of government to regulate or to prohibit. Thus, in the

leading case on balancing, Konigsberg v. State Bar of California, 131 the Court upheld the refusal of the State to certify an applicant for

admission to the bar. Required to satisfy the Committee of Bar Examiners that he was of “good moral character,” Konigsberg testified that he

did not believe in the violent overthrow of the government and that he had never knowingly been a member of any organization which

advocated such action, but he declined to answer any question pertaining to membership in the Communist Party.

For the Court, Justice Harlan began by asserting that freedom of speech and association were not absolutes but were subject to various

limitations. Among the limitations, “general regulatory statutes, not intended to control the content of speech but incidentally limiting its

unfettered exercise, have not been regarded as the type of law the First or Fourteenth Amendment forbade Congress or the States to pass,

when they have been found justified by subordinating valid governmental interests, a prerequisite to constitutionality which has necessarily

involved a weighing of the governmental interest involved.” 132 The governmental interest involved was the assurance that those admitted to

the practice of law were committed to lawful change in society and it was proper for the State to believe that one possessed of “a belief, firm

enough to be carried over into advocacy, in the use of illegal means to change the form” of government did not meet the standard of fitness.

1047 133 On the other hand, the First Amendment interest was limited because there was “minimal effect upon free association

occasioned by compulsory disclosure” under the circumstances. “There is here no likelihood that deterrence of association may result from

foreseeable private action . . . for bar committee interrogations such as this are conducted in private. . . . Nor is there the possibility that the

State may be afforded the opportunity for imposing undetectable arbitrary consequences upon protected association . . . for a bar applicant’s

exclusion by reason of Communist Party membership is subject to judicial review, including ultimate review by this Court, should it appear that

such exclusion has rested on substantive or procedural factors that do not comport with the Federal Constitution.” 134

Balancing was used to sustain congressional and state inquiries into the associations and activities of individuals in connection with allegations

of subversion 135 and to sustain proceedings against the Communist Party and its members. 136 In certain other cases, involving state

attempts to compel the production of membership lists of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and to investigate

that organization, use of the balancing test resulted in a finding that speech and associational rights outweighed the governmental interest

claimed. 137 The Court used a balancing test in the late 1960’s to protect the speech rights of a public employee who had criticized his

employers. 138 On the other hand, balancing was not used when the Court struck down restrictions on receipt of materials mailed from

Communist countries, 139 and it was similarly not used in cases involving picketing, pamphleteering, and demonstrating in public places.

140 But the only case in which it was specifically rejected involved a statutory regulation like those which had given rise to the test in the first

place.

1048 United States v. Robel 141 held invalid under the First Amendment a statute which made it unlawful for any member of an

organization which the Subversive Activities Control Board had ordered to register to work in a defense establishment. 142 Although

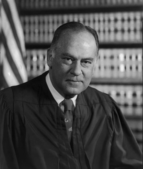

Chief Justice Warren for the Court asserted that the vice of the law was that its proscription operated per se “without any need to

establish that an individual’s association poses the threat feared by the Government in proscribing it,” 143 the rationale of the decision was

not clear and present danger but the existence of less restrictive means by which the governmental interest could be accomplished. 144 In a

concluding footnote, the Court said: “It has been suggested that this case should be decided by ‘balancing’ the governmental interests . . .

against the First Amendment rights asserted by the appellee. This we decline to do. We recognize that both interests are substantial, but we

deem it inappropriate for this Court to label one as being more important or more substantial than the other. Our inquiry is more

circumscribed. Faced with a clear conflict between a federal statute enacted in the interests of national security and an individual’s exercise of

his First Amendment rights, we have confined our analysis to whether Congress has adopted a constitutional means in achieving its

concededly legitimate legislative goal. In making this determination we have found it necessary to measure the validity of the means adopted

by Congress against both the goal it has sought to achieve and the specific prohibitions of the First Amendment. But we have in no way

‘balanced’ those respective interests. We have ruled only that the Constitution requires that the conflict between congressional power and

individual rights be accommodated by legislation drawn more narrowly to avoid the conflict.” 145

The “Absolutist” View of the First Amendment, With a Note on “Preferred Position”.—During much of this period, the opposition to the

balancing test was led by Justices Black and Douglas, who espoused what may be called an “absolutist” position, denying the

government any power to abridge speech. But the beginnings of such a philosophy may be gleaned in much earlier cases in which a rule of

decision based on a preference for First Amendment liberties was prescribed. Thus, Chief Justice Stone in his famous Carolene Products

“footnote 4” suggested that the ordinary presumption of constitutionality which prevailed when economic

1049 regulation was in issue might very well be reversed when legislation which restricted “those political processes which can

ordinarily be expected to bring about repeal of undesirable legislation” is called into question. 146 Then in Murdock v. Pennsylvania, 147 in

striking down a license tax on religious colporteurs, the Court remarked that “[f]reedom of press, freedom of speech, freedom of religion are in

a preferred position.” Two years later the Court indicated that its decision with regard to the constitutionality of legislation regulating

individuals is “delicate . . . [especially] where the usual presumption supporting legislation is balanced by the preferred place given in our

scheme to the great, the indispensable democratic freedoms secured by the First Amendment. . . . That priority gives these liberties a sanctity

and a sanction not permitting dubious intrusions.” 148 The “preferred–position” language was sharply attacked by Justice Frankfurter in

Kovacs v. Cooper 149 and it dropped from the opinions, although its philosophy did not.

Justice Black expressed his position in many cases but his Konigsberg dissent contains one of the lengthiest and clearest expositions of it.

150 That a particular governmental regulation abridged speech or deterred it was to him “sufficient to render the action of the State

unconstitutional” because he did not subscribe “to the doctrine that permits constitutionally protected rights to be ‘balanced’ away whenever a

majority of this Court thinks that a State might have an interest sufficient to justify abridgment of those freedoms . . . I believe that the First

Amendment’s unequivocal command that there shall be no abridgment of the rights of free speech and assembly shows that the men who

drafted our Bill of Rights did all the ‘balancing’ that was to be done in this field.” 151 As he elsewhere wrote: “First Amendment rights are

beyond abridgment either by legislation that directly restrains their exercise or by suppression or impairment through harassment,

1050 humiliation, or exposure by government.” 152 But the “First and Fourteenth Amendments . . . take away from government,

state and federal, all power to restrict freedom of speech, press and assembly where people have a right to be for such purpose. This does not

mean however, that these amendments also grant a constitutional right to engage in the conduct of picketing or patrolling whether on publicly

owned streets or on privately owned property.” 153 Thus, in his last years on the Court, the Justice, while maintaining an “absolutist” position,

increasingly drew a line between “speech” and “conduct which involved communication.” 154

Of Other Tests and Standards: Vagueness, Overbreadth, Least Restrictive Means, and Others.—In addition to the foregoing tests, the Court

has developed certain standards that are exclusively or primarily applicable in First Amendment litigation. Some of these, such as the doctrines

prevalent in the libel and obscenity areas, are very specialized, 155 but others are not. Vagueness is a due process vice which can be brought

into play with regard to any criminal and many civil statutes, 156 but as applied in areas respecting expression it also encompasses concern

that protected conduct will be deterred out of fear that the statute is capable of application to it. Vagueness has been the basis for voiding

numerous such laws, especially in the fields of loyalty oaths, 157 obscenity, 158 and restrictions on public demonstrations. 159 It is usually

combined with the overbreadth doctrine,

1051 which focuses on the need for precision in drafting a statute that may affect First Amendment

rights; 160 an overbroad statute that sweeps under its coverage both protected and unprotected speech and conduct will normally be struck

down as facially invalid, although in a non–First Amendment situation the Court would simply void its application to protected conduct. 161

Similarly, and closely related at least to the overbreadth doctrine, the Court has insisted that when the government seeks to carry out a

permissible goal and it has available a variety of effective means to the given end, it must choose the measure which least interferes with

rights of expression. 162 Also, the Court has insisted that regulatory measures which bear on expression must relate to the achievement of

the purpose asserted as its justification. 163 The prevalence of these standards and tests in this area would appear to indicate that while

“preferred position” may have disappeared from the Court’s language it has not disappeared from its philosophy.

Is There a Present Test?—Complexities inherent in the myriad varieties of expression encompassed by the First Amendment guarantees of

speech, press, and assembly probably preclude any single standard.

1052 For certain forms of expression for which protection is claimed, the Court engages in “definitional balancing” to determine

that those forms are outside the range of protection. 164 Balancing is in evidence to enable the Court to determine whether certain covered

speech is entitled to protection in the particular context in which the question arises. 165 Utilization of vagueness, overbreadth and less

intrusive means may very well operate to reduce the occasions when questions of protection must be answered squarely on the merits.

What is observable, however, is the re–emergence, at least in a tentative fashion, of something like the clear and present danger standard in

advocacy cases, which is the context in which it was first developed. Thus, in Brandenburg v. Ohio, 166 a conviction under a criminal

syndicalism statute of advocating the necessity or propriety of criminal or terroristic means to achieve political change was reversed.

The prevailing doctrine developed in the Communist Party cases was that “mere” advocacy was protected but that a call for concrete, forcible

action even far in the future was not protected speech and knowing membership in an organization calling for such action was not protected

association, regardless of the probability of success. 167 In Brandenburg, however, the Court reformulated these and other rulings to mean

“that the constitutional guarantees of free speech and free press do not permit a State to forbid or proscribe advocacy of the use of force or of

law violation except where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such

action.” 168 The Court has not revisited these is sues since Brandenburg

1053 so the long–term significance of the decision is yet to be determined. Freedom of Belief

The First Amendment does not expressly speak in terms of liberty to hold such beliefs as one chooses, but in both the religion and the

expression clauses, it is clear, liberty of belief is the foundation of the liberty to practice what religion one chooses and to express oneself as

one chooses. 169 “If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be

170 orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein.”

Speaking in the context of religious freedom, the Court at one point said that while the freedom to act on one’s beliefs could be limited, the

freedom to believe what one will “is absolute.” 171 But matters are not so simple.

Flag Salute Cases.—That government generally may not compel a person to affirm a belief is the principle of the second Flag Salute

Case. 172 In Minersville School District v. Gobitis, 173 the Court upheld the power of the State to expel from its schools certain children,

Jehovah’s Witnesses, who refused upon religious grounds to join in a flag salute ceremony and recitation of the pledge of allegiance.

“Conscientious scruples have not, in the course of the long struggle for religious toleration, relieved the individual from obedience to a general

law not aimed at the promotion or restriction of religious beliefs.” 174 But three years later, a six–to–three majority of the Court reversed

itself. 175

1054 Justice Jackson for the Court chose to ignore the religious argument and to ground the decision upon freedom of speech.

The state policy, he said, constituted “a compulsion of students to declare a belief. . . . It requires the individual to communicate by word and

sign his acceptance of the political ideas [the flag] bespeaks.” 176 But the power of a State to follow a policy that “requires affirmation of a

belief and an attitude of mind” is limited by the First Amendment, which, under the standard then prevailing, required the State to prove that the

act of the students in remaining passive during the ritual “creates a clear and present danger that would justify an effort even to muffle

expression.” 177

However, the principle of Barnette does not extend so far as to bar government from requiring of its employees or of persons seeking

professional licensing or other benefits an oath generally but not precisely based on the oath required of federal officers, which is set out in the

Constitution, that the taker of the oath will uphold and defend the Constitution. 178 It is not at all clear, however, to what degree the

government is limited in probing the sincerity of the person taking the oath. 179

Imposition of Consequences for Holding Certain Beliefs.—Despite the Cantwell dictum that freedom of belief is absolute, 180 government has

been permitted to inquire into the holding of certain beliefs and to impose consequences on the believers, primarily with regard to its own

employees and to licensing certain professions. 181 It is not clear what precise limitations the Court has placed on these practices.

1055 In its disposition of one of the first cases concerning the federal loyalty security program, the Court of Appeals for the District

of Columbia asserted broadly that “so far as the Constitution is concerned there is no prohibition against dismissal of Government employees

because of their political beliefs, activities or affiliations.” 182 On appeal, this decision was affirmed by an equally divided Court, it being

impossible to determine whether this issue was one treated by the Justices. 183 Thereafter, the Court dealt with the loyalty–security program

in several narrow decisions not confronting the issue of denial or termination of employment because of beliefs or “beliefs plus.” But the same

issue was also before the Court in related fields. In American Communications Ass’n v. Douds, 184 the Court was again evenly divided

over a requirement that, in order for a union to have access to the NLRB, each of its officers must file an affidavit that he neither believed in,

nor belonged to an organization that believed in, the overthrow of government by force or by illegal means. Chief Justice Vinson thought

the requirement reasonable because it did not prevent anyone from believing what he chose but only prevented certain people from being

officers of unions, and because Congress could reasonably conclude that a person with such beliefs was likely to engage in political strikes

and other conduct which Congress could prevent. 185 Dissenting, Justice Frankfurter thought the provision too vague, 186

Justice Jackson thought that Congress could impose no disqualification upon anyone for an opinion or belief which had not manifested

itself in any overt act, 187 and Justice Black thought that government had no power to penalize beliefs in any way. 188

1056 Finally, in Konigsberg v. State Bar of California, 189 a

majority of the Court was found supporting dictum in Justice Harlan’s opinion in which he justified some inquiry into beliefs, saying that “[i]t

would indeed be difficult to argue that a belief, firm enough to be carried over into advocacy, in the use of illegal means to change the form of

the State or Federal Government is an unimportant consideration in determining the fitness of applicants for membership in a profession in

whose hands so largely lies the safekeeping of this country’s legal and political institutions.”

When the same issue returned to the Court years later, three five–to–four decisions left the principles involved unclear. 190 Four Justices

endorsed the view that beliefs could not be inquired into as a basis for determining qualifications for admission to the bar; 191 four Justices

endorsed the view that while mere beliefs might not be sufficient grounds to debar one from admission, the States were not precluded from

inquiring into them for purposes of determining whether one was prepared to advocate violent overthrow of the government and to act on his

beliefs. 192 The decisive vote in each case was cast by a single Justice who would not permit denial of admission based on beliefs alone but

would permit inquiry into those beliefs to an unspecified extent for purposes of determining that the required oath to uphold and defend the

Constitution could be taken in good faith. 193 Changes in Court personnel following this decision would seem to leave the questions

presented open to further litigation.

Right of Association

“It is beyond debate that freedom to engage in association for the advancement of beliefs and ideas is an inseparable aspect of the ‘liberty’

assured by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which embraces freedom of speech. . . . Of course, it

1057 is immaterial whether the beliefs sought to be advanced by association pertain to political, economic, religious or cultural

matters, and state action which may have the effect of curtailing the freedom to associate is subject to the closest scrutiny.” 194 It would

appear from the Court’s opinions that the right of association is derivative from the First Amendment guarantees of speech, assembly, and

petition, 195 although it has at times seemingly been referred to as a separate, independent freedom protected by the First Amendment. 196

The doctrine is a fairly recent construction, the problems associated with it having previously arisen primarily in the context of loyalty–security

investigations of Communist Party membership, and these cases having been resolved without giving rise to any separate theory of

association. 197

Freedom of association as a concept thus grew out of a series of cases in the 1950’s and 1960’s in which certain States were attempting to

curb the activities of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. In the first case, the Court unanimously set aside a

contempt citation imposed after the organization refused to comply with a court order to produce a list of its members within the State.

“Effective advocacy of both public and private points of view, particularly controversial ones, is undeniably enhanced by group association, as

this Court has more than once recognized by remarking upon the close nexus between the freedoms of speech and assembly.” 198

“[T]hese indispensable liberties, whether of speech, press, or association,” 199 may be abridged by governmental action either directly or

indirectly, wrote Justice Harlan, and the State had failed to demonstrate a need for the lists which would outweigh the harm to associational

rights which disclosure would produce.

Applying the concept in subsequent cases, the Court again held in Bates v. City of Little Rock, 200 that the disclosure of membership lists,

because of the harm to be caused to “the right of association,” could only be compelled upon a showing of a subordinating interest; ruled

in Shelton v. Tucker, 201 that while a State had a broad interest

1058 to inquire into the fitness of its school teachers, that interest did not justify a regulation requiring all teachers to list all

organizations to which they had belonged within the previous five years; again struck down an effort to compel membership lists from the

NAACP; 202 and overturned a state court order barring the NAACP from doing any business within the State because of alleged

improprieties. 203 Certain of the activities condemned in the latter case, the Court said, were protected by the First Amendment and, while

other actions might not have been, the State could not so infringe on the “right of association” by ousting the organization altogether. 204

A state order prohibiting the NAACP from urging persons to seek legal redress for alleged wrongs and from assisting and representing such

persons in litigation opened up new avenues when the Court struck the order down as violating the First Amendment. 205

“[A]bstract discussion is not the only species of communication which the Constitution protects; the First Amendment also protects vigorous

advocacy, certainly of lawful ends, against governmental intrusion. . . . In the context of NAACP objectives, litigation is not a technique of

resolving private differences; it is a means for achieving the lawful objectives of equality of treatment by all government, federal, state and

local, for the members of the Negro community in this country. It is thus a form of political expression. . . .

“We need not, in order to find constitutional protection for the kind of cooperative, organizational activity disclosed by this record, whereby

Negroes seek through lawful means to achieve legitimate political ends, subsume such activity under a narrow, literal conception of freedom of

speech, petition or assembly. For there is no longer any doubt that the First and Fourteenth Amendments protect certain forms of orderly

group activity.” 206

1059 This decision was followed in three subsequent cases in which the Court held that labor unions enjoyed First Amendment

protection in assisting their members in pursuing their legal remedies to recover for injuries and other actions. In the first case, the union

advised members to seek legal advice before settling injury claims and recommended particular attorneys; 207 in the second the union

retained attorneys on a salary basis to represent members; 208 in the third, the union maintained a legal counsel department which

recommended certain attorneys who would charge a limited portion of the recovery and which defrayed the cost of getting clients together with

attorneys and of investigation of accidents. 209 Wrote Justice Black: “[T]he First Amendment guarantees of free speech, petition, and

assembly give railroad workers the rights to cooperate in helping and advising one another in asserting their rights. . . .” 210

Thus, a right to associate together to further political and social views is protected against unreasonable burdening, 211 but the evolution of

this right in recent years has passed far beyond the relatively narrow contexts in which it was given birth.

Social contacts that fall short of organization or association to “engage in speech” may be unprotected, however. In holding that a state may

restrict admission to certain licensed dance halls to persons between the age of 14 and 18, the Court declared that there is no “generalized

right of ‘social association’ that includes chance encounters in dance halls.” 212

In a series of three decisions, the Court explored the extent to which associational rights may be burdened by nondiscrimination

1060 requirements. First, Roberts v. United States Jaycees 213 upheld application of the Minnesota Human Rights Act to

prohibit the United States Jaycees from excluding women from full membership. Three years later in Board of Directors of

Rotary Int’l v. Rotary Club of Duarte, 214 the Court applied Roberts in upholding application of a similar California law to prevent Rotary

International from excluding women from membership. Then, in New York State Club Ass’n v. New York City, 215 the Court upheld against

facial challenge New York City’s Human Rights Law, which prohibits race, creed, sex, and other discrimination in places “of public

accommodation, resort, or amusement,” and applies to clubs of more than 400 members providing regular meal service and supported by

nonmembers for trade or business purposes. In Roberts, both the Jaycees’ nearly indiscriminate membership requirements and the State’s

compelling interest in prohibiting discrimination against women were important to the Court’s analysis. On the one hand, the Court found,